I have a varied, some would say bizarre, reading list. Everything from popular fiction to science (in every branch) to fairy tales to dictionaries and encyclopaedias to old books of all kinds. Some very old books indeed.

Hello, my name’s CJ and I’m a Smooth-Reader.

I found Distributed Proofreaders just over five years ago, and fell in love. I’ve always spotted the misspellings and iffy punctuation in the books I read, and here was my chance to be as nitpicking as I wanted with nobody to tell me I was peculiar. In fact, everyone else was like me. So I couldn’t be that odd after all.

I started like everyone else, checking that the text we produce matches the original book as closely as possible. I graduated to putting formatting codes around text that needed it, and two months after signing up I did my first Smooth-Read. I’ve now read 146 books and I’m looking forward to reading many more.

It’s great to be part of a team effort like this, doing something as worthwhile as preserving all these old texts. I like it that we don’t just work on the classics of literature and the “big” scientific texts that everybody knows about. All those less known books deserve saving too—and can be more interesting because they’ve been forgotten. I love that I can talk about a shared interest to people from the USA to the Philippines, and Australia to Hawaii—as well as nearer to home in the UK. Whatever the time of day or night there’s always someone around. (Don’t tell anyone, but there’s fun stuff too—like word games and jokes.)

What was my first Smooth-Read? It was a set of three plays by Olive Dargan, The Mortal Gods and Other Plays, published in 1912. After reading them, I felt we ought to have let the playwright remain in obscurity. I didn’t like it at all, and this piece of dialogue should explain why. (Phania, allegedly an adult, is speaking to her father and, sadly, this is typical of her conversational style.)

Pha. Lose me? O, never, daddy, never! I’m

Your pipsey, wipsey, umpsey, ownty own!

It didn’t put me off Smooth-Reading, however, and eight days later I sent in comments on something much more enjoyable—The Eighteenth Century in English Caricature by Selwyn Brinton. During the rest of the year, I read adventures and romances, fairy tales from China and Russia, science fiction, essays, archaeology, healthcare, history, science and cookery.

2010 brought a new list of books—more fiction of all sorts, biographies, political pamplets and books. I think my favourite of the whole year (and competition was fierce) was Jacko and Jumpo Kinkytail (The Funny Monkey Boys), a collection of bedtime stories for young children. Most of it was read while on a train home from work. My journey wasn’t normally that long, but something happened on the way home—something I felt compelled to share with the poor post-processor of the book.

I’m stuck on a train. Someone’s thrown a large tractor tyre on the tracks, we hit it at speed and everything rattled and shook and jumped, we did an emergency stop and then everything went off. The engine’s badly damaged (no fuel, water or oil, no electrics or anything) and we’re sat in a wooded cutting waiting for rescue. They’ve put detonators (yes, detonators!!) on the track ahead of us so that the relief train knows when it’s getting near. Oh—and it’s hot—very hot. I was going to the theatre tonight, having saved up for the ticket, but it starts in an hour, so even if the train arrives now, we can’t get to the town where I live in time for me to get home and back.

I also shared the progress of the rescue effort as I read on. At twenty past seven the rescue train arrived (three hours after we’d set off) and we were transferred to it. At eight o’clock the police declared it a crime scene and we weren’t allowed to leave. Finally, at ten past eight, we were on our way.

Hooray for Smooth-Reading—I would have been as bored as the rest of the passengers after three and a half hours on a stationary train in a heatwave. Instead, I walked into my house that night having done on the train what I would normally do in an evening at home, making the commute part of my leisure time instead of lost hours.

Among the books I read in 2011 were an account of explorers and missionaries in Africa and a compilation of Creole proverbs (two of which were far too indelicate for our sensitive compiler to translate into English). There were also fiction, natural history, political tirades, magazines, and a book on etiquette.

In the following year I had a bit of a break, while I did other things, but at the end of the year I picked up a some fascinating books from the 15th and 16th centuries that brought history to life. The first was a couple of volumes of The Paston Letters, a collection of letters, wills and other documents relating to an influential Norfolk family between 1422 and 1509. It gives an insight into not just the political events of the time, but also domestic concerns and family quarrels that sound very modern.

Aultman & Taylor Friction Clutch

The second was the first volume of Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland. This overview of Britain as it was in 1587, and the history of how it got there, is informative, entertaining, even chatty. The author wanders off the topic, and then comes back saying “now, where was I again?” You get anecdotes, recipes and gossip in with your history and the description of every aspect of life in Elizabethan England.

2013 brought a new crop, including books about apples, George Washington’s first military campaign, Vasco da Gama’s first voyage and handicrafts for boys. There were works by Erasmus and Galileo, a somewhat gruesome (but informative) book on amputation from 1764 and a variety of novels.

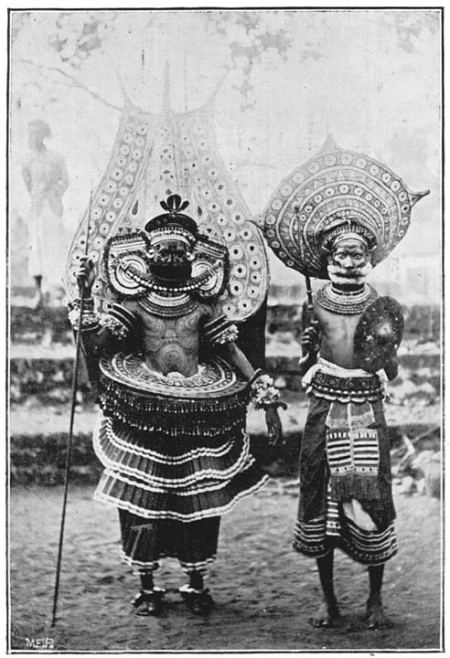

A standout was Farm Engines and How to Run Them: The Young Engineer’s Guide, containing the most amazing technical drawings, of which my favourite is the one to the right. I think it’s the combination of the hugely detailed part and the outline drawing of the surrounding engine that attracts me. It’s worth downloading this book for the pictures alone.

This is why I love Smooth-Reading. There are so many different things to read that, whatever you like, you’re bound to find something you’ll enjoy. So do give it a go. You never know what you’ll discover.

I’m looking forward to what the next year will bring me to read, but in the meantime, I’ll just return to that philosophy book and an adventure novel from 1921.

Posted by LCantoni

Posted by LCantoni