25 years of dilemmas

When I signed up on 18 January 2001 on a new and exciting website with the then-unfamiliar name Distributed Proofreaders, I couldn’t imagine I would still be there 25 years later, with over 1200 ebooks posted to Project Gutenberg. That is almost one per week, over the entire period.

The basic Distributed Proofreaders ebook production model is simple: Using scanned page images and OCR text provided by a Content Provider, volunteers proofread and format one page at a time in three proofreading rounds and two formatting rounds. Then a Post-Processor assembles the completed pages into an ebook that is submitted to the Project Gutenberg collection. My primary roles at Distributed Proofreaders are Content Provider and Post-Processor.

Instead of talking about all the niceties of the process, let me delve into the dilemmas I have faced while working as a volunteer for such a long time.

What content to provide

Obtaining interesting books to process into ebooks can be a real challenge. Although in most cases we are forced to work with books that are about a century old or older, I often try to find books that have a link with current events. When a calamity hits a certain region, I often try to find books about that region, especially if that book provides some background to the events. The earthquake in Haiti prompted me to look up some books about that island nation’s curious history. The Russian invasion of Ukraine inspired me to collect a range of works on that embattled country, such as Ukraine, the Land and Its People.

Apart from that, I often turn to my long-time favorites: exploration, anthropology, folklore, nature, and science in general, and works related to India or the Philippines in particular, including The Reign of Greed, an English translation of the powerful 1887 novel by Filipino nationalist José Rizal, which remains required reading in Filipino schools. (I also provided the ebook version of the Dutch translation of this important work, Noli me tangere: Filippijnsche roman.)

To buy or not to buy

Antique books can be expensive, so buying books to scan and run at Distributed Proofreaders is often out of the question. My most significant source of physical books over the years has been thrift stores, but what you can buy there is often very limited. Good finds are rare, but not impossible, and require a regular quick scan. About five or six thrift shops are within half an hour’s cycling distance from my home or office in the Netherlands, which makes them reachable during a lunch break. The second most important source are online classifieds. Books from that source tend to be cheaper than professional book stores. My normal strategy is not to look for a particular title, but to go through the book racks or online classifieds and ask myself, is this eligible (clears copyright, no duplicate), is this doable, and does it add value to the Project Gutenberg collection? If so, I will buy the book, mostly for just a few euros.

Unfortunately, certain categories of books are far more likely to end up in thrift stores. Nice old illustrated books on nature are a rare find, whereas old children’s books are relatively common. Classic (or former classic) novels take a middle position, and a large bulk are religious texts, which I normally don’t run.

To scan or to download

In the early days, before large archives of scans like the Internet Archive appeared online, just downloading a scan-set wasn’t an option: everything had to be scanned by hand. Over the years, I think I’ve owned more than six or seven different scanners, all with their own quirks and abilities. Next to the books themselves, they are the biggest investment, and most aren’t made to last many thousands of pages.

Scanning takes a lot of time. However, the benefit of self-scanning is twofold. Obviously, if a book has not been scanned before, you have no choice, and you can truly make something more available immediately. But even with previously scanned books, having the illustrations available in high resolution, and without the compression artifacts or vignetting caused by the overhead scanners used for the large projects, helps to get a better end-result.

It may be a surprise for some, but the most time spent on preparing ebooks does not go into correcting or formatting text, but rather in the processing of scanned illustrations. Since I like heavily illustrated works, and some individual images can take up to an hour to clean up, those images add up to more hours than any other activity.

Dutch or English or …

My native language is Dutch and I like to prepare Dutch books for processing at Distributed Proofreaders. Having enough material available for Dutch volunteers, and having enough Dutch volunteers for those books, is always a bit of a catch-22. Without books, the volunteers won’t come, and without volunteers, the books will stall in the rounds. For now, I try to balance them out, half Dutch, half English, and a small sprinkling of other languages in between. When I run a Dutch book, I will try to find an English edition of the same work, and run them close to each other. My special interest goes to English translations of Dutch works.

To duplicate effort or not

In the early days, Project Gutenberg was one of the few places that offered fully digitized ebooks. You had a few other sites, often with just a few texts, concentrating on one subject or author. This too has changed. Large government-subsidized repositories have been created. For Dutch, we have the Digital Library of Dutch Literature (DBNL), which includes full-text transcriptions of thousands of books. It seems quite pointless to duplicate that work at Distributed Proofreaders. However, there are several reasons I would still sometimes pick up a book that has already been done elsewhere:

- Legal. Project Gutenberg has a very liberal terms-of-use license that places almost no restrictions on reuse, whereas other archives may dubiously claim copyright or (in the EU) database rights on the texts they offer. It is nice to have a copy of an ebook available without such encumbrances.

- Accessibility. Project Gutenberg has some strict rules that make ebooks more accessible: a single HTML and plain text file, only using mature and stable technology, and without active components. This is a big boon for accessibility, and linked to that is:

- Durability. Project Gutenberg has been around for over half a century, and probably will remain around for an even longer time. I have seen many ebook projects come and go, and disappear completely from the net.

- Quality. The ebooks at Project Gutenberg that were prepared by Distributed Proofreaders are often of better quality than those available at other collections. For a few works I’ve duplicated from other ebook repositories, I’ve used software to find all relevant differences between ours and theirs, and I collected pretty exact statistics on errors in both versions. It was satisfying to find far fewer errors in the Distributed Proofreaders versions, demonstrating the care our volunteers take in the five proofreading and formatting rounds.

Hard or easy

As long-timers at Distributed Proofreaders will know, I don’t shy away from difficult works, such as the Fornander Collection of Hawaiian Antiquities and Folk-Lore (see this blog post for details on how this challenging ebook was prepared). The value added by manually proofreading difficult works is often much higher than for straightforward texts like novels. On the other hand, it is also good to have easy works like novels available. Those are great for beginning volunteers and are easy to post-process, so they allow me to regularly complete works, while the hard works slowly progress through the rounds and later through post-processing.

To finish the old or to start something new

I am a hopeless procrastinator. Having over 100 projects in the rounds at Distributed Proofreaders, I still have plenty of urges to start new projects, as new interesting books cross my path and more subjects need exploration. At the same time, I know several large projects are languishing in post-processing. They are hard, often needing a few final but boring steps to get up to my quality standards. Being a perfectionist, I often have to remind myself of that saying of Voltaire, “Le mieux est l’ennemi du bien,” the perfect is the enemy of the good. Then I try to make the ebook good enough and get it posted. Any remaining issues can better be seen and solved by the eyes and hands of the collective when it is out in the open. Still, it took me years to consider my posted texts fully ready for public consumption, as there still might be some comma confused for a period hiding in a text, or some odd OCR confusion surviving in the deep catacombs of a book.

Hobby or family

Finally, perhaps the biggest dilemma of all: to spend time on Distributed Proofreaders, or with my family. The kids are grown up now and have found their own place, but still want to get some assistance from their father once in a while, and my wife won’t appreciate being a “computer widow,” so joint activities are always on the table. And, of course, the elephant in the room: the bills need to be paid, so a full-time job is needed as well. Those high priorities are not dilemmas at all.

What motivates me…

All these dilemmas are practical ones, but after 25 years the more interesting question may be why I keep returning to this work at all.

All human beings, in a way, crave some kind of recognition, and most people build their own little cathedrals in one form or another. There is a short story by Tolkien, “Leaf by Niggle,” which explores some themes of that trait. In it, an artist paints a large tree, but his work is neither understood nor appreciated, and work on it is often frustrated by everyday needs. In the end, only one small leaf remains, framed and hung in the corner of a local museum. That already is more than most people will ever achieve. Nomen est omen, and my own name being derived from that of St. Jerome, the patron saint of librarians, it is perhaps obvious that my little cathedral would be a library.

We live in a world where text is often deemed outdated or superfluous, swamped by the flood of images and sounds that modern technology spews upon us at an unprecedented rate. I believe that idea is mistaken. Text is fixed speech: condensed, polished, and refined. It is the closest we can come to immortalizing our thoughts. The act of writing not only fixes those thoughts in a medium, but also forces us to rethink them, confronts us with their inconsistencies, and makes them available for others to scrutinize, critique, and improve. That is why I believe text is not going away, and why reading will remain an important activity.

Thoughts are dangerous. Thoughts are infectious: they motivate us, empower others, and as a result have often been suppressed. Libraries collect thoughts—condensed into text, bundled into books. Libraries are, in a sense, the antithesis of suppression. They are built to share thoughts, to collect often conflicting ideas and allow them to stand side by side, so that other minds can absorb them, scrutinize them, see their contradictions, and produce something new from the result. Libraries may even inspire and help movements to end injustice and bring social change.

Access to knowledge should not be a privilege. Underprivileged communities should be able to access historical works that are hard to find, works that hold their own heritage but are locked away in expensive tomes, stored in imposing buildings, and located in faraway countries. Page scans only go halfway in that respect, as fully proofread texts are far more accessible—an aspect that is particularly important for disabled people. Digitization is not only about preserving cultural heritage; it is about making it accessible, affordable, and ubiquitous, and in doing so keeping culture, and cultural diversity, alive.

My selection of texts is impulsive, as explained above, but little by little the library is growing—and I am learning and enjoying the work. Even better, I am not alone. For 25 years, I have shared this effort with the many wonderful volunteers at Distributed Proofreaders. That, too, is a great motivation: to be part of a community of like-minded individuals working toward a common goal, while holding widely diverging opinions on many other subjects—more like a bazaar than a cathedral.

This post was contributed by Jeroen Hellingman, a Distributed Proofreaders volunteer.

Posted by LCantoni

Posted by LCantoni

Abraham Fornander was born in Sweden, on the island of Öland, on 4 November 1812, the son of a clergyman. He studied theology at the University of Uppsala, but dropped out and left Sweden to became a whaler. In 1838, he arrived on Hawaii. Here, he became a coffee planter, land-surveyor, and journalist. He also officially became a citizen of the (then still independent) Kingdom of Hawaii, and married Pinao Alanakapu, a Hawaiian chiefess. He started to promote public education and took up various official roles as inspector, governor, and judge. This allowed him to travel on the Hawaiian islands and collect a lot of information about Hawaiian mythology and the Hawaiian language. He used much of his collected materials to publish his Account of the Polynesian Race (a work I hope to tackle at some later date). After his death, he left a massive collection of notes and papers. These ended up in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum and ultimately were published, together with English translations, from 1916 to 1920. The

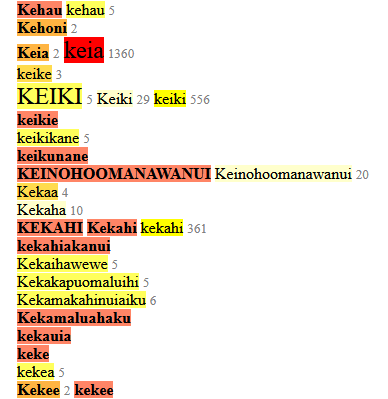

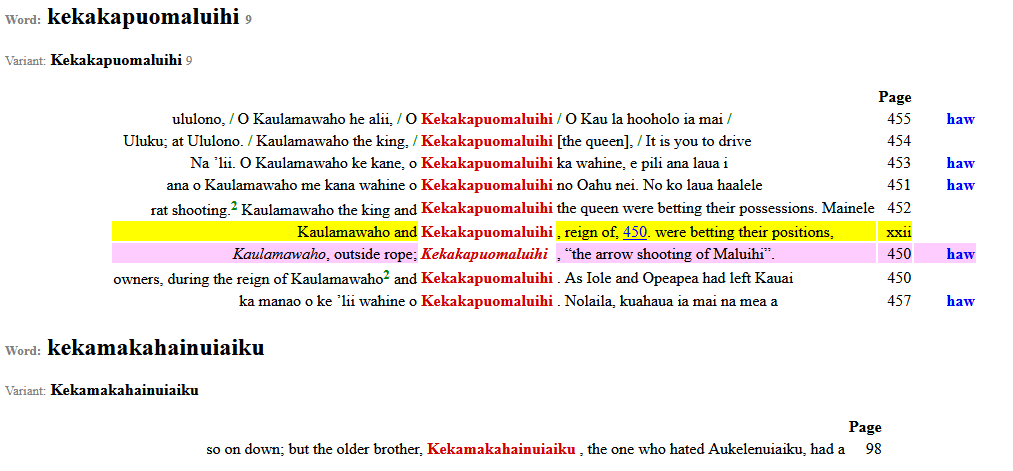

Abraham Fornander was born in Sweden, on the island of Öland, on 4 November 1812, the son of a clergyman. He studied theology at the University of Uppsala, but dropped out and left Sweden to became a whaler. In 1838, he arrived on Hawaii. Here, he became a coffee planter, land-surveyor, and journalist. He also officially became a citizen of the (then still independent) Kingdom of Hawaii, and married Pinao Alanakapu, a Hawaiian chiefess. He started to promote public education and took up various official roles as inspector, governor, and judge. This allowed him to travel on the Hawaiian islands and collect a lot of information about Hawaiian mythology and the Hawaiian language. He used much of his collected materials to publish his Account of the Polynesian Race (a work I hope to tackle at some later date). After his death, he left a massive collection of notes and papers. These ended up in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum and ultimately were published, together with English translations, from 1916 to 1920. The  Luckily, I’ve done this a few times before, and developed a few tools to help me make this easier. During my preparation, I tagged each fragment of text in my file with the language it is written in. This enables me to create word-lists, which I can inspect. Words that occur many times can be safely ignored, but those that are rare or unique may need some further inspection. Since I color-code by frequency, rare words jump out.

Luckily, I’ve done this a few times before, and developed a few tools to help me make this easier. During my preparation, I tagged each fragment of text in my file with the language it is written in. This enables me to create word-lists, which I can inspect. Words that occur many times can be safely ignored, but those that are rare or unique may need some further inspection. Since I color-code by frequency, rare words jump out.

When I was a child, I had one of those big treasury-type books of nursery rhymes and fairy tales called Young Years, published in 1960. I say “I” had it, but really I had to share it with my younger brother, whose main interest in it was embellishing the text with abstract crayon art. It didn’t need his help, because it was already lavishly illustrated in a variety of styles. I loved the pictures as much as I loved the stories.

When I was a child, I had one of those big treasury-type books of nursery rhymes and fairy tales called Young Years, published in 1960. I say “I” had it, but really I had to share it with my younger brother, whose main interest in it was embellishing the text with abstract crayon art. It didn’t need his help, because it was already lavishly illustrated in a variety of styles. I loved the pictures as much as I loved the stories.