At Distributed Proofreaders, we are all volunteers. We are under no time pressure to proof a certain number of pages, lines or characters. When we check out a page, we can take our careful time to complete it.

At Distributed Proofreaders, we are all volunteers. We are under no time pressure to proof a certain number of pages, lines or characters. When we check out a page, we can take our careful time to complete it.

We can choose a character-dense page of mind-numbing lists of soldier’s names, ship’s crews, or index pages. We are free to select character-light pages of poetry, children’s tales or plays. Of course these come with their own challenges such as punctuation, dialogue with matching quotes or stage directions. We can pick technical manuals with footnotes, history with side notes, or science with Latin biology names. We can switch back and forth to chip away at a tedious book interspersed with pages from a comedy or travelogue.

Every so often though, I stop and think about the original typesetters.

They didn’t get to pick their subject material, their deadline or their quota. They worked upside-down and backwards. They didn’t get to sit in their own home in their chosen desk set-up, with armchair, large screen, laptop or other comforts. Though we find errors in the texts that they set, many books contain very few of these errors. When I pause between tedious pages, I wonder how they did it.

Beyond the paycheck, what motivated them to set type on the nth day of the nnth page of a book that consisted mostly of lists, or indices? Even for text that would be more interesting to the typesetter, the thought of them having to complete a certain number of pages in a given day to meet a printing deadline is just impressive.

I know many have jobs today that require repetitive activities. But how many are so detail-oriented, with no automation, that leave a permanent record of how attentive you were vs. how much you were thinking about lunch? Maybe it was easier to review and go back and fix errors than I picture it to be. Maybe they got so they could set type automatically and be able to think of other things or converse.

I know many have jobs today that require repetitive activities. But how many are so detail-oriented, with no automation, that leave a permanent record of how attentive you were vs. how much you were thinking about lunch? Maybe it was easier to review and go back and fix errors than I picture it to be. Maybe they got so they could set type automatically and be able to think of other things or converse.

When I’m proofing a challenging page, I sometimes think of that person who put those letters together for that page. I realize my task is so much easier. If I want I can stop after that page and hope some other proofer will do a page or two before I pick up that project again. I can stop, eat dinner, and come back tomorrow to finish the page when I’m fresh.

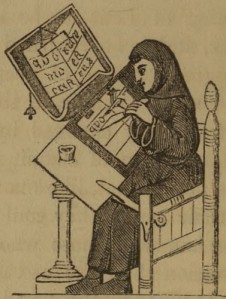

I imagine a man standing at a workbench with his frames of letters and numbers and punctuation at one side, picking out the type one by one, hoping that the “I” box doesn’t contain a misplaced “l” or “1.” I see him possibly thinking about how much easier life is for him than it was for the medieval scribe. The scribe was working on a page for days, weeks, even months, one hand-drawn character at a time. I see the typesetter appreciating how much improved his own life is and how much more available his work makes books to his current readers. And I smile as I see him smile.

This post was contributed by WebRover, a DP volunteer.

Love this, WebRover. I’m a wannabe typesetter from way back and I too often think about the people who worked on the pages, sometimes wondering if the page might have been the apprentice’s first solo effort, or the master in a hurry to get home to the family, through to maybe hours of extra time and effort expended to ensure continuity and consistency. In some books it is simply amazing how few errors there are. Thank you and Linda so much.

I think about typesetters and scribes, too! My husband and I have written a couple of family histories, using our computer’s word processor for both words and photos. It is not an easy task. We took turns reading the pages aloud to each other, with shorthand words for punctuation. It was amazing how many typos we caught–and how many more made it through three rounds of checking!

A friend of ours worked on a Linotype machine. He said it was a vast improvement over the old way of doing typesetting, and was a real timesaver.

I am always amazed when I read an old book that has no errors. What pride that typesetter took in his work! I wish people today still took such pride in their productions.

Beautiful thoughts, beautiful words. We need them very much. Thanks, WR.

Olive.

Reblogged this on Vauquer Boarding House and commented:

Very interesting post by WebRover, a volunteer at Distributed Proofreaders.

Yes, a very interesting post, but also one that gives me an opportunity to thank you and the other volunteers for the pleasure I’ve had in reading some of these old texts, thanks to the work you do.

I have many happy memories of the rows of backwards letters and numbers from the good-old-days all waiting to create words and meaning on some fresh, new pieces of paper at my dad’s printing shop. I can almost smell the chemical fragrances of the different areas and hear the sounds of the presses. The printing has all moved out of town now, since the Heidelberg press went down. My dad adapted to become solely a graphic designer for the last 10 years of his career, so he was better off than some, but his time in the business was a time of great changes. We’ve lost something wonderful in our march toward modernity. Thank you for taking me down memory lane.