When Distributed Proofreaders recently celebrated its 25th Anniversary, its volunteers were given a rich array of special projects to work on involving the number 25. Among these projects is a fascinating booklet published circa 1525: Here foloweth a lytell treatyse of the beaute of women.

This Lytell Treatyse states that it is a translation from a French book, “la beaute de femmes,” by an unnamed author. Not much is known about its English translator/printer/publisher, Richard Fawkes, whose last name is spelled in various sources as Faques and Fakes. We do know that he had a bookshop in Durham Rents in London, behind Durham House, then a Tudor royal residence on the Strand.

The Lytell Treatyse is rendered entirely in rhymed verse, with, as was customary at the time, little punctuation and lots of variant spellings. It begins with an invocation to Mary, the mother of Jesus, in whom both beauty and goodness “were perfaytely assembled.” He begs her to guide his hand so that the unidentified gentleman who asked him to do the translation is happy with it. He claims to be inexperienced with women himself, so he will “folow the sentence” of the French book rather than give his own opinions. He names pairs of classical lovers, such as Troilus and Cressida, Helen of Troy and Paris, and Tristan and Isolde, whose love affairs were sparked by the woman’s beauty, “what euer foloweth of the consequence” (a reference to the fact that these affairs ended in disaster).

During this era, some writers came up with aesthetic criteria in the form of “triads” of female attributes constituting beauty. The Lytell Treatyse begins with a triad of “Symple [i.e., modest] manyer and countenaunce” (how she acts), “Symple regade” (how she looks at others), and “Symple answer” (how she talks). It touches upon a woman’s physical form, praising “hygh” points such as a high forehead, a head held high “The better therwyth hyr hat she doeth vpholde,” and “brestes hygh fayre and rounde wyth fyne gorgias well and fayre couert” (i.e., well covered with fine material). It also notes “lowe” points, such as “lowe laughying,” a “lowely regarde” (harking back to the “Symple regade” mentioned earlier), and “whan she shall neese [sneeze] to make the sounde but lowe.” In all, the author lists eight sets of three attributes comprising ideal beauty.

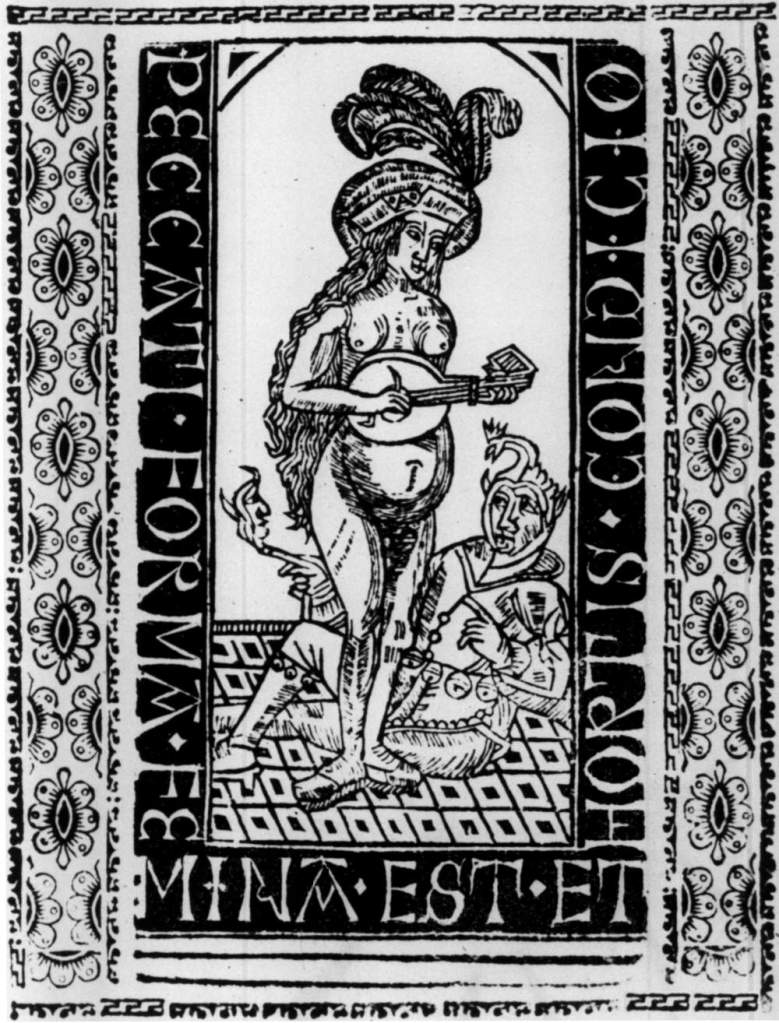

But in the final stanzas the author repeats, three times, the French moral of the story: “Beaulte sans bonte ne vault rien” (beauty without goodness is worth nothing.) And that brings us to the rather odd woodcut adorning the Lytell Treatyse. It depicts a voluptuous woman wearing nothing but a fancy plumed hat and slippers, playing a lute to a jester sitting at her feet. The Latin inscription in its border, “Peccati forma femina est et mortis condicio,” can be translated roughly as, “Sin and death take the shape of woman.” This apparent reminder that men can be fools for beautiful women seems to contradict the praise of beauty in the Lytell Treatyse, but perhaps it was meant as a counterpoint to its conclusion that “beaulte with bonte assembled in a place / Gyue demonstrance of an especyall grace.”

This blog post was contributed by Linda Cantoni, a Distributed Proofreaders volunteer.

Posted by LCantoni

Posted by LCantoni