What do the Rosetta Stone, mummies, and a self-made scholar have in common?

Answer: The British Museum, which has the second largest collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts in the world (the largest is in Cairo), with over 100,000 pieces. And the self-made scholar, E.A. Wallis Budge, was one of the collection’s most important curators in the late 19th to early 20th Centuries. Thanks to the volunteers at Distributed Proofreaders and Project Gutenberg, you can explore the collection as it was in 1909, along with just about every aspect of ancient Egyptian life and history, with A Guide to the Egyptian Collections in the British Museum, Budge’s comprehensive overview.

Budge was born in 1857 into a working-class family. He left school at age 12 to work as a bookseller’s clerk. Young Budge studied Hebrew and Syriac in his spare time, and frequented the British Museum, eventually becoming acquainted with the head of Oriental Antiquities there. With his help, Budge learned Assyrian, studied cuneiform tablets in the Museum’s collection, and had access to the Museum’s library. He spent his lunch hours studying at St. Paul’s Cathedral, where the organist took an interest in him and arranged for him to go to Cambridge University on a private scholarship. Budge studied ancient languages there until 1883, when he went to work for the British Museum. He became an expert at acquiring antiquities for the museum, contributing over 11,000 objects. He ultimately rose to become the head of its Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, where he served until his retirement in 1924.

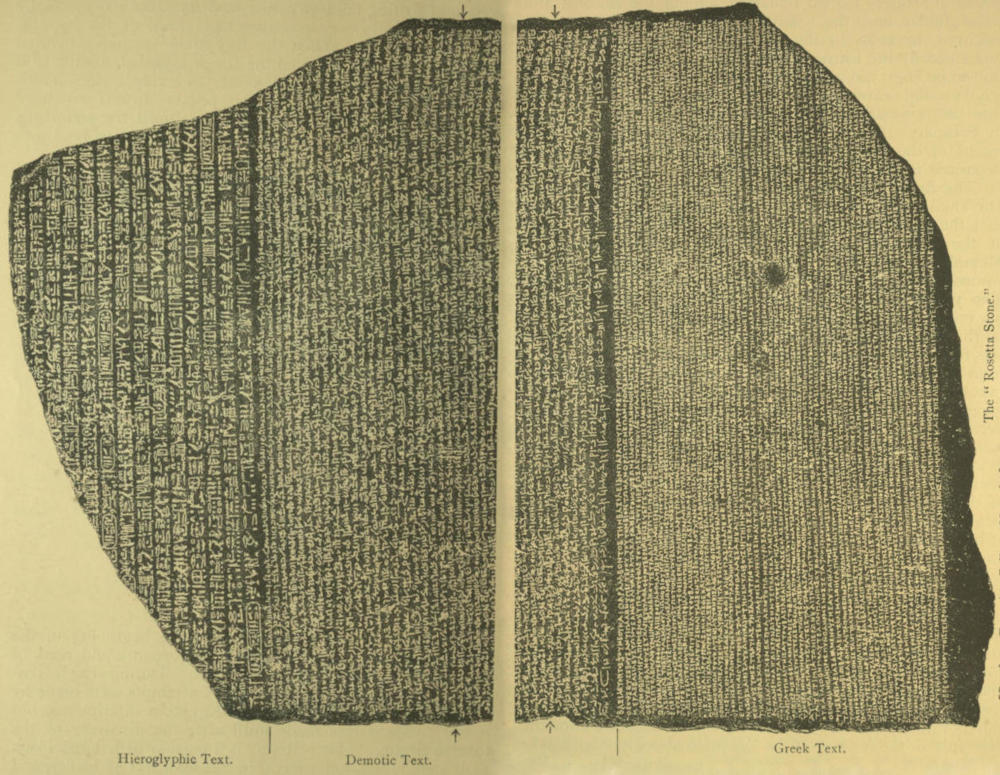

When Budge’s guide was published in 1909, the British Museum had nearly 50,000 objects in its Egyptian collection. The guide gives a fascinating overview of important items such as the Rosetta Stone, one of the jewels of the collection. This fragment from a larger stele, created in about 196 B.C., contains three inscriptions in three different scripts: Egyptian hieroglyphs; Demotic, which was used mainly for documents; and Ancient Greek. Budge describes how over the course of two decades, scholars painstakingly worked at deciphering these inscriptions. He explains that royal Egyptian names like Ptolemy and Cleopatra were decipherable from cartouches on the stone. Budge notes that it was not until 1822 that French scholar Jean-François Champollion “drew up classified lists of the hieroglyphics, and formulated a system of grammar and general decipherment which is the foundation upon which all subsequent Egyptologists have worked.”

Budge’s guide is lavishly illustrated with 53 plates and 180 other illustrations throughout the text. But it is much more than just a catalog of objects and their descriptions. As Budge notes, the collection “illustrates, in a more or less comprehensive manner, the history and civilization of the Egyptians from the time when their country was passing out of the Predynastic Period under a settled form of government, about B.C. 4500, to the time of the downfall of the power of the Queens Candace at Meroë, in the Egyptian Sûdân, in the second or third century after Christ.” Based on the collection, he is able to give a vivid, detailed picture of ancient Egypt’s history and geography, languages and literature, manners and customs, art and architecture, religion and science, and every schoolchild’s favorite subject, mummies and their tombs.

The text of Budge’s guide is filled with Egyptian hieroglyphs, as well as latinized Egyptian words, Coptic, and Ancient Greek. In preparing the text for Project Gutenberg, Distributed Proofreaders was fortunate to have the help of volunteers who are experts in ancient languages. They helped ensure that these parts of the text have been correctly rendered. Thanks to Distributed Proofreaders teamwork, you can enjoy this fascinating and accessible account of ancient Egypt for free.

This post was contributed by Linda Cantoni, a Distributed Proofreaders volunteer.

Posted by LCantoni

Posted by LCantoni