When searching for works to prepare as e-books at Distributed Proofreaders, I always try to find works that are still interesting today, add some diversity to Project Gutenberg’s collection, or are of significant cultural or historical importance.

Another criterion is that the works should be manageable by the volunteers here at Distributed Proofreaders, and in this, I like to explore the edges of what is possible. Each e-book on the site goes through multiple proofreading and formatting rounds, with volunteers carefully reviewing the images of each page with the computer-generated text generated from the images. Once all the pages have completed these steps, a post-processor carefully assembles them into an e-book.

Collections of folklore are always popular and interesting. They are timeless and offer an insight into the culture of a people. Over the years, I’ve added a couple of books with Hawaiian folklore from various authors, and, while digging deeper for more, I hit upon the mother-lode of many of these works: the Fornander Collection of Hawaiian Antiquities and Folk-Lore, a huge collection of material collected in the late 19th Century by Abraham Fornander, published between 1916 and 1920, in three large volumes, by the Bishop Museum Press in Honolulu.

Abraham Fornander was born in Sweden, on the island of Öland, on 4 November 1812, the son of a clergyman. He studied theology at the University of Uppsala, but dropped out and left Sweden to became a whaler. In 1838, he arrived on Hawaii. Here, he became a coffee planter, land-surveyor, and journalist. He also officially became a citizen of the (then still independent) Kingdom of Hawaii, and married Pinao Alanakapu, a Hawaiian chiefess. He started to promote public education and took up various official roles as inspector, governor, and judge. This allowed him to travel on the Hawaiian islands and collect a lot of information about Hawaiian mythology and the Hawaiian language. He used much of his collected materials to publish his Account of the Polynesian Race (a work I hope to tackle at some later date). After his death, he left a massive collection of notes and papers. These ended up in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum and ultimately were published, together with English translations, from 1916 to 1920. The first volume of Fornander’s collection is now available on Project Gutenberg (the following two volumes are still in progress at Distributed Proofreaders at the time of writing).

Abraham Fornander was born in Sweden, on the island of Öland, on 4 November 1812, the son of a clergyman. He studied theology at the University of Uppsala, but dropped out and left Sweden to became a whaler. In 1838, he arrived on Hawaii. Here, he became a coffee planter, land-surveyor, and journalist. He also officially became a citizen of the (then still independent) Kingdom of Hawaii, and married Pinao Alanakapu, a Hawaiian chiefess. He started to promote public education and took up various official roles as inspector, governor, and judge. This allowed him to travel on the Hawaiian islands and collect a lot of information about Hawaiian mythology and the Hawaiian language. He used much of his collected materials to publish his Account of the Polynesian Race (a work I hope to tackle at some later date). After his death, he left a massive collection of notes and papers. These ended up in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum and ultimately were published, together with English translations, from 1916 to 1920. The first volume of Fornander’s collection is now available on Project Gutenberg (the following two volumes are still in progress at Distributed Proofreaders at the time of writing).

The volumes are bilingual, with the English translation on the left and Hawaiian original on the right. Since the Hawaiian language, as written at that time, used only standard letters and no diacritics, it is not that difficult for non-speakers to deal with. In fact, the Hawaiian alphabet is surprisingly short, with just 13 letters: five vowels: a e i o u (each with a long pronunciation and a short one, but here not distinguished); eight consonants: h k l m n p w; and the glottal stop (not shown in this text). Since all syllables in Hawaiian are a single consonant followed by a vowel or diphthong, to non-natives some words may appear long and repetitious, and in particular names can become pretty long — although there are also plenty of very short words to compensate.

Like many indigenous languages, Hawaiian is an endangered language. It was still widely spoken in the 19th Century, when the Hawaiian islands were an independent kingdom that maintained diplomatic relations with many countries. The Hawaiian Kingdom’s constitution was written in Hawaiian. Literacy was promoted and newspapers were regularly printed. However, through the machinations of American businessmen, the government of Queen Liliʻuokalani was overthrown in 1893, and after being run as a “Republic” for a short while, the territory was annexed by the United States in 1898. This led to the demise of the Hawaiian language. In 1896, English was made the sole official language, and the use of Hawaiian in schools was systematically suppressed. Only in the 1950’s did this trend slowly begin to reverse, with renewed interest in the language and indigenous culture, though Hawaii became a U.S. state in 1959. Hawaiian dictionaries were published, and a revival movement gained traction in the 1970’s, with schools once again teaching children the language. However, it is still spoken by only a small fraction of the current population of Hawaii.

Having Fornander’s collection easily accessible will be very valuable to learners of the language (even though the language used is probably archaic and the spelling differs a bit from modern Hawaiian) and to students of its folklore and history. The collection starts off, appropriately, with a mythological description of the discovery of the islands and the origins of the Hawaiian people. The first volume further includes, among many others, the popular story of Umi, a fifteenth-century chief or king, who usurped the throne from his older half-brother, then ruled for about 35 years and united the Hawaiian islands into a single kingdom.

Since today only about 24,000 speakers of Hawaiian remain, the hope of finding enough native speakers to help us out with this project was limited. We needed to ask non-Hawaiian-speaking volunteers to work on Hawaiian pages, even if they didn’t know a single word. Hawaiian is an Austronesian language, remotely related to languages such as Malay or Tagalog, so speakers of those might occasionally recognize a word, although it will often require some linguistic training to see the relationship (and that really is no help in proofreading those pages). Hawaiian is more closely related to Polynesian languages such as Tongan, Samoan, or Tahitian, and speakers of those languages can probably get some of the gist of the stories (but speakers of those languages are also not easily found).

So how to deal with such a massive and complex work?

Well, first, praise where praise is due: The many volunteers at Distributed Proofreaders dutifully ploughed through the Hawaiian pages and fixed a lot of errors left behind by the optical character recognition process (which turns scanned images into editable text). When I received the work to post-process, most of the hard work had already been done.

Still, post-processing a work like this is a considerable challenge. Post-processors have to create both text and HTML files for Project Gutenberg and make them both easily readable. First, I needed to untwine the English and Hawaiian text (which in the original book were on alternating pages), such that both the English and Hawaiian text became continuous texts, at least at the chapter level. To do this I simply made two copies of the text file, and then removed the English part of the text. Then I recombined them, so that the Hawaiian follows the corresponding English chapter.

Once the untwining was done, I started to add tags to demarcate chapter headings, poetry, tables, and footnotes, convert quotation marks to their proper curly shapes, etc., and deal with the issues the proofreaders noted. Then I came to the task of checking the entire text for remaining spelling issues, and that in a language I do not speak, without the help of a spelling-checker, and in an obsolete spelling.

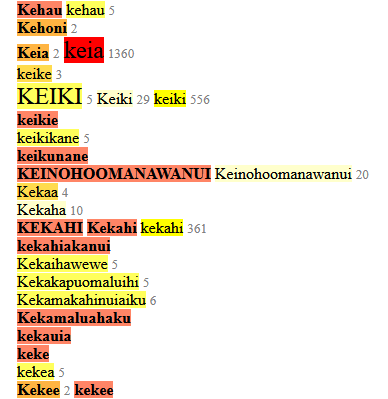

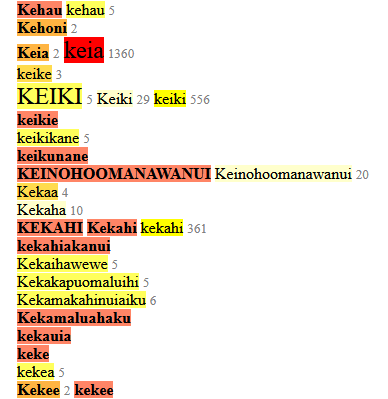

Luckily, I’ve done this a few times before, and developed a few tools to help me make this easier. During my preparation, I tagged each fragment of text in my file with the language it is written in. This enables me to create word-lists, which I can inspect. Words that occur many times can be safely ignored, but those that are rare or unique may need some further inspection. Since I color-code by frequency, rare words jump out.

Luckily, I’ve done this a few times before, and developed a few tools to help me make this easier. During my preparation, I tagged each fragment of text in my file with the language it is written in. This enables me to create word-lists, which I can inspect. Words that occur many times can be safely ignored, but those that are rare or unique may need some further inspection. Since I color-code by frequency, rare words jump out.

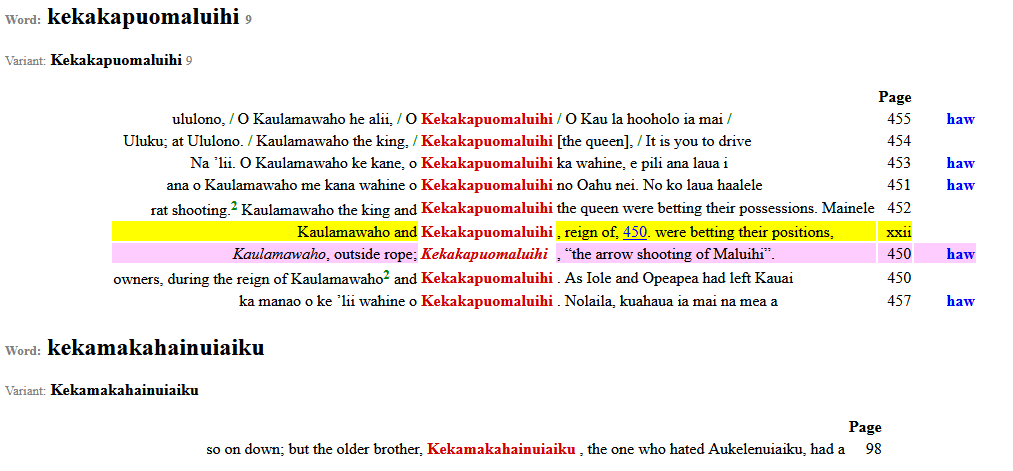

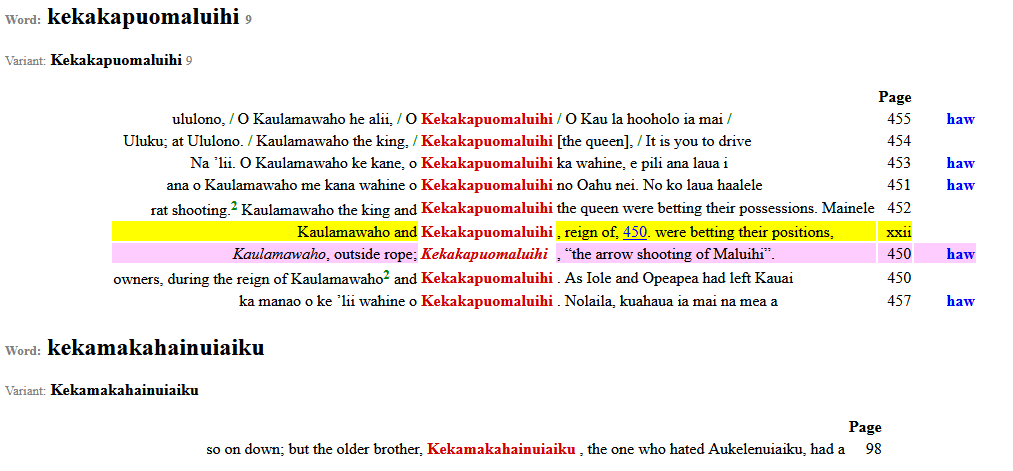

Using the word-list, I can identify suspect words, but that doesn’t always help. Then I can turn to a another tool and generate a KWIC (Keyword in Context) index. This allows me to see how each word is used, and, based on that, I can often decide how to deal with it.

The illustration below show how this works for the name Kekakapuomaluihi. At a glance, I can see this is used in Hawaiian and English. It is mentioned in the index (yellow background), pointing to the page it can actually be found, and its meaning is explained in a footnote (pink background).

Finally, I wanted to align the text in parallel columns, such that the English and Hawaiian could be read side-by-side, as in the original. This is less straightforward than it sounds, because sometimes a paragraph on the left is the equivalent of two on the right, and sometimes paragraph boundaries do not match. To make this work, I give all paragraphs in one language a label, and give the matching paragraphs in the other language the same label. This way, my software knows which paragraphs to place next to each other.

Having gone through all those steps, I was at last able to submit the work to Project Gutenberg. Now the first volume of Fornander’s monumental collection is freely available to all those interested in Hawaiian culture. At the time of writing, volume two is almost ready as well, and volume three is in the final formatting round at Distributed Proofreaders.

This post was contributed by Jeroen Hellingman, a Distributed Proofreaders volunteer who was the Project Manager and Post-Processor for the Fornander Collection.

Posted by LCantoni

Posted by LCantoni

Abraham Fornander was born in Sweden, on the island of Öland, on 4 November 1812, the son of a clergyman. He studied theology at the University of Uppsala, but dropped out and left Sweden to became a whaler. In 1838, he arrived on Hawaii. Here, he became a coffee planter, land-surveyor, and journalist. He also officially became a citizen of the (then still independent) Kingdom of Hawaii, and married Pinao Alanakapu, a Hawaiian chiefess. He started to promote public education and took up various official roles as inspector, governor, and judge. This allowed him to travel on the Hawaiian islands and collect a lot of information about Hawaiian mythology and the Hawaiian language. He used much of his collected materials to publish his Account of the Polynesian Race (a work I hope to tackle at some later date). After his death, he left a massive collection of notes and papers. These ended up in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum and ultimately were published, together with English translations, from 1916 to 1920. The

Abraham Fornander was born in Sweden, on the island of Öland, on 4 November 1812, the son of a clergyman. He studied theology at the University of Uppsala, but dropped out and left Sweden to became a whaler. In 1838, he arrived on Hawaii. Here, he became a coffee planter, land-surveyor, and journalist. He also officially became a citizen of the (then still independent) Kingdom of Hawaii, and married Pinao Alanakapu, a Hawaiian chiefess. He started to promote public education and took up various official roles as inspector, governor, and judge. This allowed him to travel on the Hawaiian islands and collect a lot of information about Hawaiian mythology and the Hawaiian language. He used much of his collected materials to publish his Account of the Polynesian Race (a work I hope to tackle at some later date). After his death, he left a massive collection of notes and papers. These ended up in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum and ultimately were published, together with English translations, from 1916 to 1920. The  Luckily, I’ve done this a few times before, and developed a few tools to help me make this easier. During my preparation, I tagged each fragment of text in my file with the language it is written in. This enables me to create word-lists, which I can inspect. Words that occur many times can be safely ignored, but those that are rare or unique may need some further inspection. Since I color-code by frequency, rare words jump out.

Luckily, I’ve done this a few times before, and developed a few tools to help me make this easier. During my preparation, I tagged each fragment of text in my file with the language it is written in. This enables me to create word-lists, which I can inspect. Words that occur many times can be safely ignored, but those that are rare or unique may need some further inspection. Since I color-code by frequency, rare words jump out.