In Barbara Tuchman’s The Proud Tower, there is a chapter (“End of a Dream”) about America’s decision to become a colonial power. At the time, we had just won the Spanish-American war and there was a major political conflict between those that believed that America was destined to become an imperial power (the pro-imperialism forces) and those that believed that becoming an imperial power would destroy America’s principals of self-government and isolation (the anti-imperialism forces). The pro-imperialism forces won.

The political paper “Outlook: Uncle Sam’s Place and Prospects in International Politics” gives a feel for the nature of that political conflict. That paper was read by Newton MacMillan before The Fortnightly Club (Oswego, N. Y.) on May 2, 1899.

In that paper, Mr. MacMillan argued for colonization of the Philippines, in part, because it was needed to protect our interests in capturing the Chinese market. He cited statistics about the value of our exports to China and talked of conspiracies of other foreign powers to shut us out of that market.

But how long is this to continue? With our experience of tariffs we need not be reminded that low prices do not command markets. Continental Europe does not like us. We saw that during the Spanish war, and we have heard it since in various impatient declarations of hostility, at Berlin or Vienna, far more significant than official assurances of distinguished consideration. Indeed, if Germany, or France, or Russia does not openly break with us, it is because fear or prudence is stronger than inclination. The moment any one or all of them combined feels able to slam the door in our face without fear of reprisals, the door will be slammed.

He argued for setting up a base for operations against any attempts to shut us out of China.

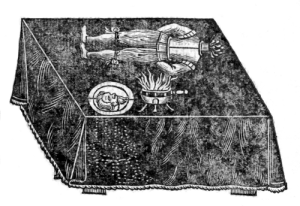

So, in great measure, the Philippines mean for us a foothold in the East and a strong leverage on China. Would our co-operation be sought at this time, as it has been, not only by England but by Germany, if George Dewey had not sailed his ships into the harbor of Manila on the night of the 30th of April, 1898, dodging the sunken mines and torpedoes, that he might on the morrow fire “the shot heard round the world?” On that day and since then the world learned that we are a nation not only of shopkeepers and money-grabbers, but also of fighters; that in a prolonged war we stand unconquerable, irresistable. A year and a day ago we were a nation; to-day we are a power, and have only to assert ourselves as such.

Then, after arguing that we must subject the Philippines to our rule for economic reasons, he argued that colonization was needed to “make us less corrupt”:

But if, on the other hand, we set up good government in the colonies, how long shall we be content with misrule at home? Not long, I promise you. “It is one of the most beautiful compensations of this life,” says the wise man, “that no man can sincerely try to help another without helping himself.” No less true is this of nations. The eyes of the world are upon us and the conscience of civilization will hold us strictly accountable. As we deal with those ignorant wards whom the God of Battles has given into our keeping, even so shall we be dealt with. And in uplifting them from barbarism so shall we be uplifted.

He even stated that:

I believe the present low tone of our internal politics to be due to the long and peaceful isolation of the Republic.

In other words, peaceful isolation is bad, but colonizing foreign lands will save our soul. Interesting arguments.

Posted by usbengoshi

Posted by usbengoshi